I began reading Ayn Rand as a senior in high school, beginning with The Fountainhead and then Atlas Shrugged. That summer of 1965, while working out of Ardmore, OK and Enid, OK on oil exploration crews, I read all of Ayn Rand's non-fiction books to that time and her newsletter with all the back issues. I thought this very good preparation for my next adventure as a freshman at Brown University.

I found a philosophy and a worldview which was similar to much of my own, but much more completely developed. I had always thought man should be moral and heroic. I had always thought that one should work very diligently to be rational and emotions were properly controlled by and educated by one's rational decisions. I had understood that very limited government was the only government compatible with reason, the sovereign rights of the individual, and the ability of man to apply his rational faculty to improving life for man on Earth. I had already understood that big government was essentially a denial of human individuality.

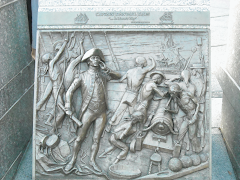

I had long understood that some principles were worth fighting for and, if necessary, dying for. My father was a naval aviator and was always a heroic presence in my life. So too were many of our nation's heroes of the French and Indian War, the American Revolution, the War with the Barbary Pirates, the Mexican War, the Civil War, some of the Indian Wars (sometimes the Indians too), WWI, WWII, and the Korean War. Those principles worth fighting for were worthily found in our Declaration of Independence and our Constitution, which were written by wise and good men. So too we had many heroes who were inventors and scientists. I had already understood that the businessman was usually honorably offering goods and services to others in voluntary trade to their mutual benefit. As such, many businessmen were heroically making human life richer, more secure, and better day after day. One of the most important things Ayn Rand and I had in common was the fact that we were both human mind and hero worshipers.

Finally, in the summer and fall of 1964, I had realized that many of the teachings of Christianity were simply wrong. I was not yet at the point of concluding that there was no reason to believe in God, but I was sure that any existent God was better than the Christian God. After reading Rand's non-fiction work, I came to the conclusion that I had no evidence for the existence of any god and that I really had no need for a god.

Basically, when I read Ayn Rand's The Fountainhead and Atlas Shrugged, I had found someone who thought along pathways similar enough to mine that her entire philosophy was useful to me in understanding my world. She had thought about the issues important to me much longer than I had and she was capable of guiding me to other issues that I needed to think about.

It turns out that 2 September has a special significance for those of us who love Atlas Shrugged. Let me repeat a post below that I wrote on 2 September 2010, while noting that it is now 66 years since she started writing it and 55 years since its publication:

On September 2, 1946, Ayn Rand began writing Atlas Shrugged and she finished her great novel in time for publication in 1957. Throughout the novel, September 2 is the date of a number of events:

- In the opening scene of the novel, a bum asking Eddie Willers for a handout, asks "Who is John Galt?" This and the way it was asked bother Eddie. As he walks through NYC, he is also bothered by the gigantic calendar hanging from a public tower and announcing the date as September 2.

- On that date, Hank Rearden and Dagny Taggart decide to take a vacation together. On that vacation they discover an abandoned motor that should have revolutionized the use of energy in the world.

- Francisco D'Anconia makes his speech on money on September 2. He proclaims money to be the tool of free trade and the result of noble effort, not the root of evil. Those who call money evil choose to replace its use with the force of the gun.

- D'Anconia Copper is nationalized on 2 September, but the date on the calendar is replaced by "Brother, you asked for it!"